This represents my notes on the presentations at the 2018 International Association for the Study of Popular Romance conference. Please consider my status as an imperfect recorder of literary academia. I hope you enjoy reading about this conference as much as I enjoyed observing it. This blog uses affiliated links.

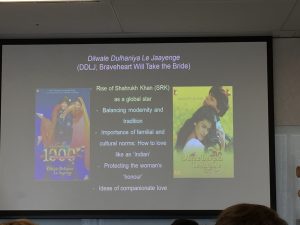

Negotiating Romantic Love in India: Family, Public Space, and Popular Cinema. Meghna Bohidar (University of Delhi)

Bohidar interviewed couples in public places in Mumbai to discover a lived experience of romance

In the 1980s and 90s, India had massive privatisation, rapid urbanisation, and improved mobility and literacy for women. Bollywood echoed these trends with many elopement stories. Many of the couples interviewed considered cinema of the 1990s to be truly romantic

- Reiterating the idea of love over lust

- Takes courage to step away from tradition

- ‘do it like Raj’ in DDLJ (Dilwale Dulhaniya Le Jaayenge – Braveheart Will Take the Bride)

(Jodi McAlister tweet) Bohidar: in Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge, the male hero respects cultural norms as well as more modern ideals of being a partner, and courage in justifying the relationship.

Relationships are often hidden in full view, as people navigate secret relationships, inspired by the culture of consumption from 90s cinema.

In the 90s, public spaces on Hindi cinema changed:

- Lalitha Gopalan’s book Cinema of Interruptions outlines this

- Heroines became more active

- More seamless integration of foreign places

- Elaborate costumes (landscapes for consumptions) in song and dance

- Family in palatial homes (good family life and aspirational for success0

- Sanitised street scenes

- Public display of affections is a fantasy

(Kat Mayo tweet) Streets were represented in 90s song and dance sequences, but they were sanitised. PDAs portrayed as fantasy – eg Kisi Disco Mein Jaaye (Let’s go to a discotheque) in which the couple searches for places to display love.

By contrast, some social commentators have shown a culture of paranoia

- Public affection is seen as anti-Indian, including the “war on Valentines Day”, and media reports of kissing couples being beaten up

- Right wing is seen as anti-modern

- Kissing seen as modern

- The ‘modern’ view on romance seen to erase caste and traditions

(Kat Mayo tweet) For the couples, navigating relationships in public spaces wasn’t so much about avoiding parental scrutiny, but the ability to be anonymous when displaying affection in public.

Lots of couples interviewed quotes songs and movies as to how to improve society, however, all couples were:

- Of the same class (self described as same taste)

- Different combinations of caste/background/language/belief systems

(Heather Schell tweet) “These days romance takes money, but we can’t afford to go out every day. So we just sit here and eat some street food.” –one of the Indian women Meghna Bohidar interviewed about modern romance.

Most couples interviewed in public were of lower middle class

- Acutely aware of their lack of money

- Romance is not consumption based (unlike rich people who bestow gifts)

Conclusion

- many themes of courage and risk

- love requires balance of modern aspiration and nostalgia for tradition.

(PopFicDoctors tweet) Such a fabulous paper by Meghna Bohidar! A great application of Bourdieu’s habitus and taste to Indian romance experiences

In conversation with Mina V. Esguerra. Kat Mayo

(Jennifer Hallock tweet) Kat is explaining why she felt #romanceclass should be represented at this conference: “a unique and relevant case study…with the pioneer of #romanceclass” that should launch inquiry into the achievements of this group

The paper opened with a video of the Romance Class ‘April Feels Day’ event.

Mina: community of Filipino authors writing in English

- no legal divorce in the Philippines which impacts on the writing of the HEA

- rising HIV in population vs highly Catholic country (hints at condom use without saying it)

- English is a language of privilege

- Urban based authors

Where did it start?

Mina: Popular books are either by American authors (in English) or by local authors in Filipino. There was a big gap in local authors writing in English. In 2013, the romance class began with 100 authors. The class includes guidelines and genre rules

- HEA

- Female agency, ie female characters must make decisions

- Removal of controlling tropes from Filipino media as conflict (controlling parent, natural disaster, other external issues/resolutions)

80 of the 100 authors have finished 170 books, with each course being around six months long (sometimes shorter)

Gaps in the market?

Mina: the first 12 books had no sex, and readers asked if it was a rule. The second class required people to write a sex scene, but only 1/3 of books published had a sex scene. For years, the authors only produced mf books, and after a session where writers were asked to write “anything but mf”, romance class has produced a non-mf anthology. The class also produced the first ever ff book in the Philippines.

Basically – if a reader notices a gap, then a class is given the gap as a challenge.

Why the shorter length?

- Novella to meet price point in the market

- Targeted at students

- Hangover form Mina’s writing (many Filipino publishers want 50,000 words)

- Most authors have a day job, and novellas make the word count achievable (lots of doctors)

What about the initiatives like live readings (click the link to see one)?

This was done to solve a marketing problem. Romance Class invited actors to read extracts. It began as an exercise to build confidence while reading aloud to each other, now the clips are used to market books and cross promote actors and their theatre performances. The writers have improved their dialogue and banter, to get better clips.

(Jodi McAlister tweet) Mayo asks about the way the #romanceclass community intersects with the performing arts community. Esguerra replies that it was originally a beta-reading project, but it’s now entertainment, and authors are writing in a certain way so it will be performed well.

The romance class doesn’t have any prizes (like RITA) to keep the collaborative community vibe.

(Jennifer Hallock tweet) Q from audience: How do you define happy ending? Mina: They agree to be together by the end of the book. Unlike other countries’ HEA, in PH b/c no divorce may mean that a proposal does not make sense. A HFN is more appropriate, especially for Mina’s books.